For the past 18 years, the Land Trust has been pursuing an ambitious goal to connect more than 50,000 acres of protected land in a U-shaped arc around Ithaca and the south end of Cayuga Lake. When the project—known as the Emerald Necklace initiative, reflecting the jewels of green space dotting the landscape—is complete, there will be an unbroken chain of protected land that will stretch from the Finger Lakes National Forest in the west to the Hammond Hill State Forest in the east.

While there are a multitude of rationales for this initiative—from protecting water quality in the area to expanding recreational opportunities—one of the most important factors driving the desire for interconnected green space is creating wildlife corridors. Connected habitats are critical for the daily and seasonal movements of wildlife amid the ever-growing encroachment of humanity.

Photo: Chris Ray

Wildlife corridors are natural areas that connect habitats that have become fragmented by human activity and development. Disjointed habitat and restricted movement resulting from roads and other development typically lead to a significant number of negative outcomes for wildlife, which include but are not limited to:

- Isolated populations and a stagnation in genetic diversity;

- Degraded ecosystems and biodiversity, including a lack of seed dispersal;

- Limited habitat buffers for protection from predators and other external threats;

- The inability to migrate due to resource scarcity, wildfires and other natural disasters, and the effects of climate change;

- Increased interaction with humankind, to the potential detriment of both.

Creating wildlife corridors is a critical solution to these issues, especially as species will need to move north due to climate change. In addition to helping provide migratory routes as ecosystems shift, the corridors are themselves a habitat for an abundance of birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects, as well as native plant species that provide cover and serve as a food source.

The idea of connecting patches of natural habitat is a core principle of the Land Trust’s mission, and this strategic focus applies throughout the Finger Lakes region, not just within the Emerald Necklace. For example, an emphasis on protecting existing farmland through conservation easements not only helps prevent subdivisions and other residential development, but also provides connectivity between other protected lands.

Human-made wildlife corridors, such as underpasses and overpasses across major highways, can help connect habitat that has been disrupted by human development while preventing potentially damaging interactions, such as collisions between animals and motor vehicles. However, the Land Trust is focused on restoring natural corridors wherever possible by protecting land that has yet to be developed or is being reclaimed by Mother Nature.

You only need to look as far as the Land Trust’s Bad Bear Hill acquisition to see an example of the organization’s resolve to connect wild lands. The Land Trust’s largest-ever property acquisition is adjacent to a state forest, which it will eventually join, and in near proximity to a wildlife management area and a state park.

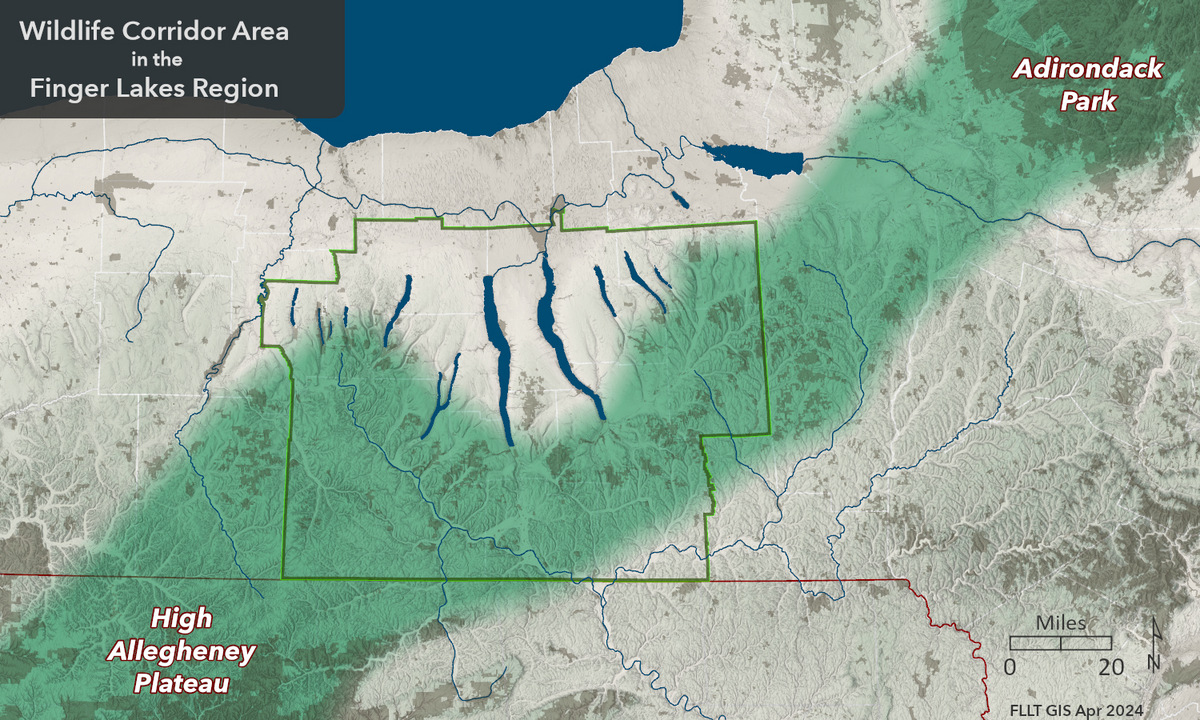

While acting to preserve and enhance habitat connectivity locally, the Land Trust is also actively involved in protecting and restoring wildlife corridors on a larger scale. The Land Trust has partnered with the Wildlands Network, the Western New York Land Conservancy, and the Nature Conservancy on a proposal for a connected landscape between the Pennsylvania Wilds region and New York’s Adirondack Mountains.

The accompanying map shows continuous habitat for wildlife to move from the Allegheny Plateau to the Adirondacks, stopping on their way through the southern portion of the Finger Lakes region. The partnership is seeking to make this linkage a major priority in the next update of the New York State Open Space Plan, as well as to incorporate a collaborative approach to connecting regional wildlife habitat.

Pulling back the lens even further, the Wildlands Network has embarked upon a comprehensive endeavor to connect wildlife habitat areas up and down the eastern seaboard. Known as the Eastern Wildway, the plan is to create wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented habitat extending from Florida in the south to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the north. The efforts of the Land Trust and its partners in Pennsylvania and New York are part of that broader plan.